Collecting Ritual Native Arts

Written by Patrick Morgan

Genuine, fake or forgery? In the field of tribal arts, these are by far, the most common questions asked of experts, whether a piece comes from Africa, Oceania or the Americas. Ultimately all tribal art artefacts will fall into one of these three categories and knowing the difference before buying is a crucial first step in building a respectable collection. Here are the expert tips on how to tell them apart!

Wabele mask, Senufo people, early 20th century. Photo: Brooklyn Museum / License CC BY 3.0

Seasoned collectors speak of having a good eye, which essentially means that they have studied the art extensively by visiting museums, galleries, private collections, the auction rooms, various art fairs and last but not least, by reading books and looking through exhibition catalogues. It can take years to understand the subtle differences between ethnographic styles, and truly see what makes a piece exceptional or merely pedestrian, but all in all, it makes for a very interesting and rewarding journey.

Treasures From The Ends Of The World

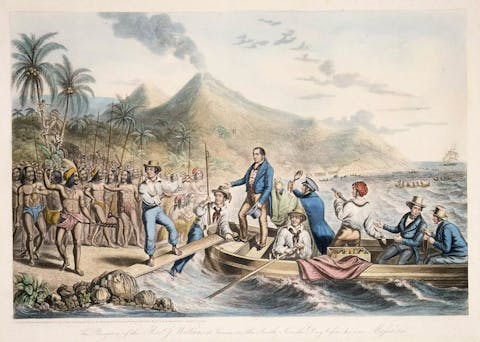

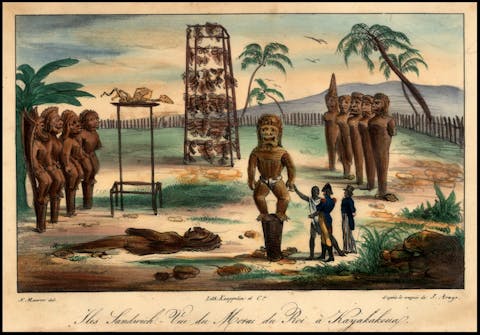

Let’s take a look at how and when these tribal artefacts were first “discovered”. At the beginning of the 16th century European explorers and missionaries began launching exploratory expeditions to the most remote regions of Africa and Oceania. This was also the beginning of the colonial exploitation of these indigenous peoples who were, up until this point, living in total isolation from the “outside world”. Their ritual laws, native arts and lifestyles were long established traditions dating back generations, if not centuries. The artefacts created and used by these peoples were important, revered objects. Their societies revolved around ancient art and the ritual way of life. Once the colonials made first contact, their cultural customs were forever altered. The Christian Missionaries encouraged the native tribes to cast off and destroy their ancient ritual arts and embrace the spiritual and societal benefits offered to those who accepted religious conversions. This was indeed the beginning of the catastrophic social conflict amongst these peoples, splitting them into groups of traditional culture and Christian culture while still living side by side.

"It can take years to understand the subtle differences between ethnographic styles, and truly see what makes a piece exceptional or merely pedestrian, but all in all, it makes for a very interesting and rewarding journey"

George Baxter, "The Reception of the Rev. J. Williams, at Tanna, in the South Seas, the Day Before He Was Massacred", 1841, National Library of New Zeeland. Image: Public Domain

John Cleveley the Younger, "Views of the South Seas: HMS Resolution and Discovery in Tahiti", 1787-1788, Image: Public Domain

Countless ancient tribal treasures dating back centuries were thrown into fires in order to “cleanse” the villagers from their heathen lifestyles, or were often traded off to the explorers passing through the regions for goods and trinkets. These once sacred objects were bartered for the modern-day miracles such as metal, cloth, medicines and guns, further corrupting and altering the lifestyles of these indigenous peoples . Once these Explorers and Missionaries returned to their homelands with stories of adventure and conquest, the crates filled with unique indigenous art objects from the furthest corners of the world were typically donated to museums or missionary societies as “curiosities”. Those items, which perhaps merited further study, were generally considered things with little or no value and typically gathered dust in the basements throughout Europe, from Portugal to Germany, for several hundred years.

Related: Learn About Oceanic Art

Re-Discovery of Tribal and Native Art

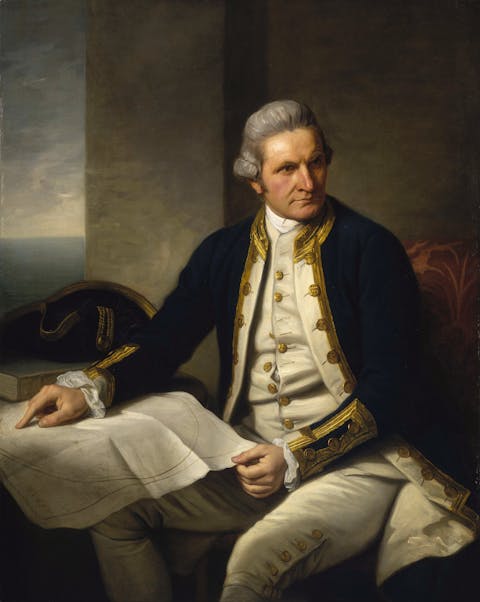

Fast forward to 1978, a Hawaiian God figure, collected by Captain James Cook, on his third voyage (1768-1779), sold for 250,000 GBP in London with Sotheby’s Auction House. This was an astronomical price for a work of “primitive art” at a time when six figure sums were reserved for important paintings or more classical art forms and not for the likes of tribal art. More than forty years later ritual native tribal art continues to soar in value, with major pieces now selling north of 10,000,000 USD.

Nathaniel Dance, Portrait of Captain James Cook (1728-79), 1776, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Greenwich Hospital Collection, Image: Public Domain

Depiction of religious ceremony on Hawaii, Jacques Arago "Iles Sandwich - Vue du Morai du Roi a Kayakakoua", 1838, Image: Public Domain

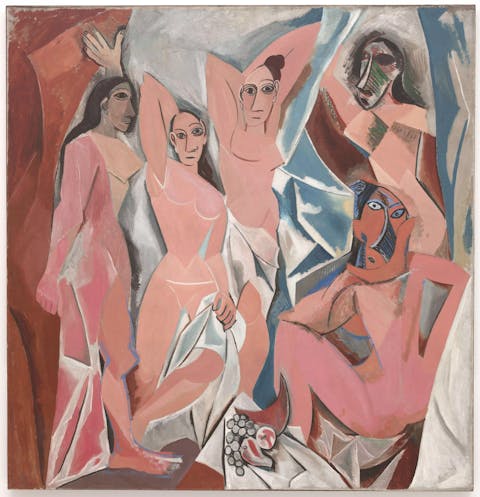

The emergence of ritual arts from native tribes on the world’s art stage began with the groundbreaking exhibition in 1935 titled “African Negro Art” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This was the first time African ritual art was presented to the art collecting elite as a medium worthy of serious appreciation in a museum setting. These formerly classified “curiosities”, with little or no value (and for the most part forgotten), were beginning to gather steam in the world of art collectors. Tribal and Native Art also had a tremendous impact on the Cubist art movement, which was introduced 25 years earlier by Pablo Picasso and George Braque. They both found inspiration in the clean, powerful, unique and expressive sculptural lines found in ritual art. It was also at this time when Dealers William Oldman and Charles Ratton opened galleries devoted to the tribal arts in London and Paris respectively, giving these long-forgotten indigenous art treasures from distant peoples' new homes amongst the world’s foremost artists and collectors.

Mbangu mask, Central Pende, Southern Bandundu, Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium, Image: Public Domain

Pablo Picasso "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon"- beginning of artists African Period, 1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Image: Public Domain

Collecting Tribal And Native Art

Between the 1940’s and 1970’s most ritual art was extremely affordable; a good 19th century Dan mask could be purchased for 50 francs in the St Germain quarter of Paris, a Fang reliquary head might sell for 500 francs and a New Ireland Uli might bring 1000 GBP in London. Savvy collectors, such as cosmetic guru Helena Rubenstein and a sculptor Jacob Epstein, as well as many others, saw the value in these amazing and important cultural works of art and built fantastic collections “for peanuts” back in the day. In today’s marketplace, native ritual art is judged not only by its artistic beauty, age and rarity, but also by its provenance. The trackable ownership history of an object adds an extraordinary value to a work of art, which was once in the collection of a major artist, museum or collector. The prices since have risen steadily over the years and now a rare masterpiece, with important provenance and of unparalleled beauty can sell for between 1,000,000 and 10,000,000 USD. And, because the native ritual arts have become so valuable in the recent years, there is a worldwide call to return these cultural treasures to their native lands. The controversial histories surrounding these repatriation requests is a subject for another in depth article addressing the colonial exploits of our forefathers and the manner in which we can rectify problems which date back centuries.

"Savvy collectors, such as cosmetic guru Helena Rubenstein and a sculptor Jacob Epstein, as well as many others, saw the value in these amazing and important cultural works of art and built fantastic collections “for peanuts” back in the day"

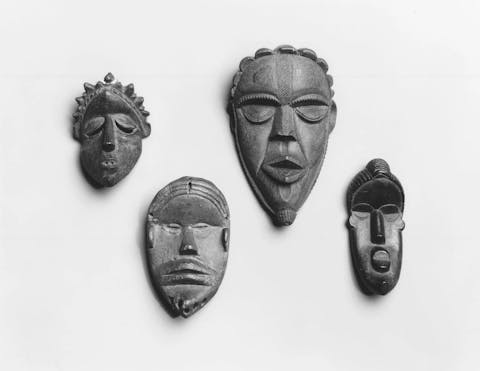

Dan personal miniature masks, 20th century, Brooklyn Museum, Image: Brooklyn Museum / License CC BY 3.0

Authentic Pieces

So, the questions remain; Is it genuine? Is it a fake? Is it a forgery? Authenticity is still the most important aspect of a tribal work of art. It defines the piece as being ritually made and used in ceremony by the indigenous peoples who created it and thereby rendering it a “genuine” or “real” piece. It is this type of piece which ultimately commands the highest price in the marketplace. A genuine piece is judged on several important points; beauty, age, rarity, patination and provenance, all of which can be faked to an expert degree. It does take a well-trained eye to understand the difference and this is the reason why provenance has become so important to collectors in recent years. he earlier mentioned Hawaiian God figure sold at Sotheby’s London in 1978 for 250,000 GBP ,collected by Captain James Cook, is what Oceanic collectors call a “pre-contact” piece, meaning it was made and used by the indigenous population long before contact with the outside world (Captain Cook was the first to discover the Hawaiian Islands). Therefore, the figure can be considered one of the purest forms of native ritual art, adhering to generations of artistic tradition prior to the influences of Western culture. If this piece came on the market today it would certainly bring 10,000,000 USD or more. It has everything a serious collector or museum is looking for: extreme rarity, beauty, age, patination and provenance. But don’t be discouraged, it is still possible to build a collection of genuine native artefacts today on a relatively modest budget. Good, genuine tribal art can still be found in flea markets, galleries and online auctions if you have a good eye and know what to look for. Chances are you can find a genuine mask or figure for a few hundred or a few thousand dollars, if you just try and focus on one area and one type of object and understand the nuances that define value. African pulleys are a very good example. They typically sell for between 300-3,000 USD and by focusing on one type of object and one specific region it is easier to gain perspective in a shorter period of time.

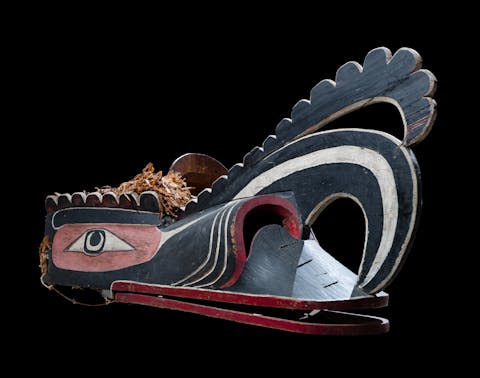

Crooked Beak of Heaven Mask, Kawakwaka'wakw, British Columbia, 19th Century, Image: Pierre Selim / License CC BY 3.0

Heddle Pulley, Senufo People late 19th or early 20th century, Brooklyn Museum, Image: Brooklyn Museum / License CC BY 3.0

Fakes

So now, what is considered a fake? It can be the type of sculpture that is typically sold on the roadside or in airports in faraway places as a souvenir. Commonly called “airport art”, it is what most travellers and tourists end up buying on trips to distant lands. The carvings are hastily made in workshops with modern tools, and produced on a massive scale. The carvings were never ritually used and have no cultural importance to the indigenous peoples. These carvings typically sell for less than ten dollars each and most of the handicraft workshops around the world have been in business since the early to mid 20th century, catering to the colonials as well as tourists.

Commercial masks for sale in a shop in the Mwenge Makonde market, Dar es Salaam. Image: Moongateclimber / License CC BY 3.0

Forgeries

This is the most dangerous category of all and I personally know a number of important Tribal Art Dealers, Collectors, as well as museum curators who have fallen prey to expertly carved forgeries, spending thousands or tens of thousands on worthless reproductions. These copies are typically carved by master carvers who adhere to the traditional styles and understand the nuances both Collectors and Dealers look for in a work of art. These are carvings meant to deceive and unless one has seen a number of similar forgeries it is quite difficult to discern the difference between what is genuine and what is not. Also, due to the astronomical prices native tribal art brings today, more and more forgeries are appearing on the market and this, again, is why provenance has become so critical in determining the value of an important work of tribal art as it brings the piece into a historically proven context via a collection date, ownership and publications, essentially creating a guarantee of authenticity.

Wooden figure, Mambila people, Nigeria, 19th/20th century, Musée du quai Branly, Paris. Image: Siren Com / CC BY-SA 3.0

To conclude, the best advice I can give to a new collector before starting a tribal art collection and after training one's eye, is to begin with modestly priced works of art (300-3000 USD) from a specific region to familiarise oneself with indigenous styles, patinas and aesthetics. Whether they be pulleys, masks or figures , you should get a feel for your taste and what pleases you most. As time goes on and you’ve trained your eye for a more important piece, remember to seek the advice from an impartial third-party expert before making a serious purchase. And once again, have fun and enjoy the journey!

Start Your Native and Tribal Art Appraisal Here!

Patrick Morgan is a Dealer and Expert in Tribal Arts who has been living in Paris since 2002. He began his career field collecting textiles and tribal artefacts in the Golden Triangle of Thailand, Laos and Burma in the late 1980’s and by 1992 was making several trips a year, exclusively to Mali, sourcing textiles and the ritual arts of the Dogon, Senufo and Bambara cultures. He began exhibiting these finds in addition to pieces from important American collections in 1998 showing at the major US Tribal Art Fairs in San Francisco, Santa Fe, New York as well as the European fairs in both Paris and Berlin. He has worked for several European auction houses as both consultant and expert.