Whose Art is it, Anyway?

written by Patrick Morgan

In the process where Western World is trying to make amends for its colonial past, many of the artworks got caught in the dispute of where they belong. Art repatriation is a delicate subject and as the objects looted during colonialism or war should be returned where they belong, the matter seems to still lack the clarity. Read more about the processes of cultural repatriation of art ant antiquities to the countries of their origin, and the influence this process has on the art market.

Brass Plaques from Benin on display in the British Museum in London. Image: Archie / Lincense: CC BY 2.0

The Provenance of Art

With the cultural repatriation movements from several countries beginning to gather steam over the last decade, can we expect important ethnographic and cultural treasures to remain in private hands in the years to come ? And do public and private museums have the power to retain their collections when countries of artistic origin demand the return of core masterpieces? Is it their duty to investigate each piece?

The ethical dilemma revolves around the acquisition histories of each and every object held in a museum's collection. How was the piece originally acquired in situ? And under what circumstances? Some of these answers we will never know, but in other circumstances the acquisition histories are well documented in the annals of colonial history.

Related: Collecting Ritual Native Arts

Trade’s Basics- Barter

Barter is a natural occurrence when two distant cultures meet. Each group essentially wants what the other has, be it rare, amazing, unusual or simply utilitarian in nature. Many important works of art and significant acquisitions have been made in this fashion, with both fair and equitable results since the dawn of time.

American Indians famously traded the island of Manhattan to the Dutch for 24 USD worth of Venetian glass trade beads. The Indians thought they got the better half of the deal because in their system of beliefs, man was not capable of “owning” land, as it is a gift from nature and the lands belong to everyone. Captain James Cook provisioned his ships in Hawaii by trading scrap metals for fish, water and other necessary items. His crew famously traded iron nails for sex.

Trade beads from ca. 1740, found in a Wichita village site in present-day Oklahoma. Image: Uyvsdi / License: CC BY-SA 3.0

The Value of Art and Cultural Heritage

Values have always been relative and this is especially so when it comes to cultural treasures. All markets are driven by supply and demand. The art market is no different, but it is also driven by beauty and emotion. And beauty has no price and is the ultimate judge.

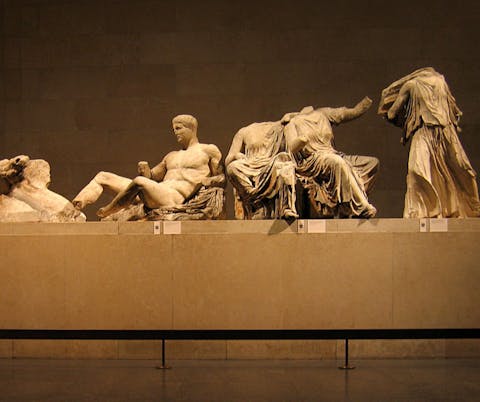

Should the Mona Lisa, the famous painting by Leonardo Da Vinci, and which is the centerpiece of the Louvre Museum in France, be returned to Italy? The Elgin Marbles, housed in the British Museum, be returned to Greece? Or the Benin Bronzes taken from the burning Palace of Oba, during a well documented colonial siege in 1897, be sent back to Nigeria ? Ethically everything should hinge on the history and circumstances surrounding acquisition of the piece in question.

Royal Palace of the 'Oba of Benin'. It is notable as the home of the Oba of Benin and other royals. The palace, built by Oba Ewedo (1255AD – 1280AD), is located at the heart of ancient City of Benin. It was rebuilt by Oba Eweka II (1914–1932) after the 1897 war with the British it was destroyed. The palace was declared a UNESCO Listed Heritage Site in 1999. The Royal Palace of Oba of Benin is a celebration and preservation of the rich Benin culture. Most of the visitors to the palace are curators, archaeologists or historians and photographers. Image: Kelechukwu Ajoku / License: CC BY-SA 4.0

World Heritage Convention

In 1954 the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property, more commonly known as the 1954 Hague Convention, was written in response to this very issue. It was the first and most comprehensive multilateral treaty dedicated exclusively to the protection of worldwide cultural heritage. In 1972 the treaty was further expanded to include endangered animals and natural habitats and is now known as the 1972 World Heritage Convention. These two landmark agreements were written to protect indigenous peoples, habitats and animals, while at the same time holding individuals and institutions accountable for their actions and collections. And now, with the advent of “Woke Culture” these issues have moved to the forefront of our ever evolving society.

"Should the Mona Lisa, the famous painting by Leonardo Da Vinci, and which is the centerpiece of the Louvre Museum in France, be returned to Italy? The Elgin Marbles, housed in the British Museum, be returned to Greece? Or the Benin Bronzes taken from the burning Palace of Oba, during a well documented colonial siege in 1897, be sent back to Nigeria? Ethically everything should hinge on the history and circumstances surrounding acquisition of the piece in question."

Repatriated Art

In 2013 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, famously returned two important 10th century Cambodian Kneeling Attendant figures, looted from the Koh Ker temple in the late 1970's, after determining they were acquired illegally by Douglas A. J. Latchford, a noted expert on Cambodian antiquities, and who was, before his death, accused of trafficking millions of dollars worth of stolen antiquities from Cambodia between the mid 1960's through the early 1990's. Since his death in 2020 his family has chosen to return their personal collections of Cambodian Art (valued at over 50 million USD), to the Cambodian people in a spirit of goodwill. These objects will become the centerpiece of a new museum in Phnom Penh dedicated to the temple arts.

Related: Learn About Oceanic Art

Lintel. Cambodia, Prasat Kok Po A (Angkor), Siem Reap Province, Preah Ko style, late 9th century, sandstone. Vishnu riding Garuda between two monstrous heads. Image: Vassil/ License: Public Domain

Returning the Art Where it Belongs

There are several solutions in the works at present to return important cultural artifacts back to the peoples of origin in a spirit of restorative justice. But there is another aspect to this dilemma. The argument that many of these rare and important cultural artifacts, collected under uncertain circumstances, and in some cases over one hundred years ago, have been preserved for future generations by bringing them into the museum fold. If these object had remained in situ, many if not most of these objects would have been destroyed by fires, floods and or the aging effects of time and exposure. And these very objects of important and reverent beauty have been elevated by these museums, giving them an important place where people the world over can see and discover the beauty of cultural art and artifacts. In turn these objects displayed in important museums around the world have attracted the attention of serious art collectors and inspired some of the most influential artistic movements of the 20th century. So by removing these objects from their countries of origin they have been placed in a spotlight of their importance and enlightened the world to the wonders of cultural diversity and beauty.

The left hand group of surviving figures from the East Pediment of the Parthenon, exhibited as part of the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum. Image: Andrew Dunn / License: CC BY-SA 2.0

Demand for Tribal Art

The dilemma named above has in turn fueled the demand for rare and beautiful tribal art in the marketplace and is directly responsible for the dramatic rise in value in recent years.

On December 24th 2020, The Musee Quai Branly returned 26 Fon artifacts, stolen from the Kingdom of Abomey in 1892 to the people of Nigeria under much fanfare. This was a highly publicized event touting the efforts of restorative justice, by French President Emmanuel Macron. In actual fact, the Musee Quai Branly has over 70,000 objects in their collections, making the return of a mere 26 objects rather insignificant. Statistically, most museums only display 5% of their holdings, meaning there will be a long road ahead for the international researchers to determine the ethics surrounding the acquisition histories within their collections.

View of the African exhibit hall at the he Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France. Image: Andreas Praefcke/ License: Public Domain

The newly built Humboldt forum in Berlin, which is Germany's largest Ethnological Museum, has announced the planned return of all 440 Benin bronzes held in its collections, to the people of Nigeria over the next several years. These are well documented works of art which were looted during the punitive siege of 1897 in Nigeria on the Palace and Kingdom of Oba by British troops led by Admiral Sir Harry Rawson.

African Exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, Germany. Image: jwyg / License: CC BY-SA 2.0

The Humboldt Forum's inaugural exhibition in September 2021, boldly confronted the issues of colonial history and it's ethical dilemmas by displaying over 20,000 objects, many of which were forcibly taken during the years of colonial expansion, each object with extensive descriptions explaining both the cultural meanings as well as the sometimes violent circumstances under which they were acquired. There are another 25 museums in Germany that house looted objects from Benin in their collections and all 25 museums have agreed to return their holdings over the next several years to the peoples of Nigeria.

" It will take decades to correct the historical wrongs committed by the colonial expansions and restricting the trade, and returning these cultural treasures to their rightful homes, is an important step in the right direction."

The two artifacts, which include a bronze cockerel and a bust that were looted from Nigeria over 125 years ago by the British military force, are placed on a table inside the Oba of Benin palace where it was looted in Benin City, mid-western, Nigeria, on February 19, 2022. - The two artifacts, which include a bronze cockerel and a bust, were part of the bronzes, ivories that were looted by British soldiers in 1897 in Benin kingdom, Edo State, Nigeria. Photo by Kola Sulaimon / AFP via Getty Images

Contradictions

Ironically, also in 2021, a world record price of 10,000,000 GBP was paid for a Benin Bronze in a deal arranged by noted Tribal Art Dealer. The controversial 16th century Benin Bronze head had been locked away in a bank vault for the last 63 years and was last purchased by prominent Tribal Art Dealer Ernst Ohly at a small London Auction house in 1951 for a few hundred pounds. The piece has been “renamed” the “Ohly” bronze and at present is in a private collection. Selling a cultural treasure with a well documented history of being looted over 100 years ago, is apparently not a crime. Not to mention the arrogance of cultural approbation by renaming an important cultural artefact after the collector who purchased it many years ago. Indeed we have a long way to go on this path of restorative justice. It will take decades to correct the historical wrongs committed by the colonial expansions and restricting the trade, and returning these cultural treasures to their rightful homes, is an important step in the right direction.

Benin bronze head from the Bode Museum in Berlin, Germany. Image: Francisco Anzola / License: CC BY-SA 2.0

Know What You Are Buying

It is important in this day and age for all collectors to thoroughly research their collections as well as potential acquisitions. The legal ramifications of purchasing looted art and / or objects made from endangered animals; elephant ivory, eagle feathers or rhinoceros horn to name a few, can lead to both the forfeiture of the object as well as criminal prosecution.

Verifying provenance through online sites such as Arkhade, a subscription service which tracks auction sales of Tribal Art back to the 1960´s, or African Heritage Documentation & Research Center, created by Guy van Rijn for Yale University, which has thousands of documented objects in its data base, as well as building a collection of auction catalogues and other historical tribal publications, can all help verify the ownership histories of various objects, in addition to due diligence in order to verify the legal status of the materials from which various objects are made, are all important responsibilities which lie upon the shoulders of today’s collectors.

On a final note, we must ask: How much longer will private and or auction sales of important and priceless cultural treasures be allowed to continue?

Start Your Native and Tribal Art Appraisal Here!

Patrick Morgan is a Dealer and Expert in Tribal Arts who has been living in Paris since 2002. He began his career field collecting textiles and tribal artefacts in the Golden Triangle of Thailand, Laos and Burma in the late 1980’s and by 1992 was making several trips a year, exclusively to Mali, sourcing textiles and the ritual arts of the Dogon, Senufo and Bambara cultures. He began exhibiting these finds in addition to pieces from important American collections in 1998 showing at the major US Tribal Art Fairs in San Francisco, Santa Fe, New York as well as the European fairs in both Paris and Berlin. He has worked for several European auction houses as both consultant and expert.