A Brief History of Chinese Art

Considering the title of this essay, you might wonder how on earth an article of just a few hundred words could possibly do justice to a subject as varied and complex as the history of Chinese Art. And it would be quite right to think this, because to encompass the artistic history of the largest nation on earth over a time span of shall we say 3522 years, is not actually possible at all. What an odd number that is and how is it arrived at, you might ask? The answer is that if you start with the Shang Dynasty around the year 1500 BC and then count the years back down to zero, then add to that the period from zero right up to 2022 AD. Keeping in mind that we are compressing such a great span of time in this China Travelogue, I am going to try to show objects which encapsulate the period in question.

Forbidden City, Beijing, China (Photo by Ran Ma via Unsplash)

The Neolithic Cultures circa 6500 BC – circa 1900 BC

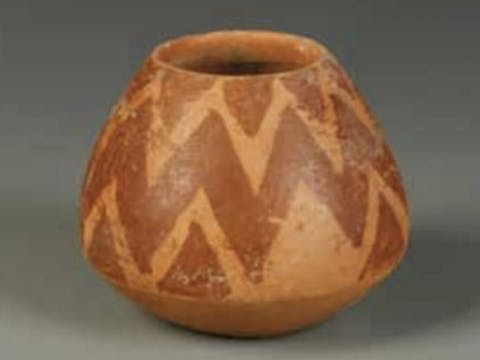

During this ancient period there were no fewer than twelve distinct chronological sub-cultures – some nomadic - from the Cishan-Peiligang (in place for 1500 years) to the Qijia (350 years). I doubt that most people would have heard of any of them. Perhaps the image that comes primarily to mind is that of often quite dynamic yet roughly made pottery vessels often with simple yet vigorous painted decoration.

Neolithic Pottery Jar. Image © Duke's

Early Kingdoms, Dynasties and Imperial China, circa 1500 BC – 1949 AD

The Shang Dynasty, circa 1500 – 1050 BC

Objects that have come down to us from the Shang are no better represented than by their fabulous bronze vessels used in ritualistic ceremonies. These objects were central to the way that Death and the hereafter was considered in China, more than a millennium before the Christian era emerged in the West. The benefit to us all, several thousand years later, lies in the fact that these artefacts were purposely buried at the time, lying undisturbed for centuries, after which time they had acquired a wonderful mature patina and brilliant encrustations as a result of their reacting – over so long a burial – to the soil in which they were first interred. The silky surfaces and colour that emerge from this natural process are truly exquisite. Later generations have tried (and conspicuously failed) to replicate these wondrous objects with crude acid bathing and paint in an attempt to equal the work of time. We are not taken in.

Shang Bronze Vessel. Image © Sotheby's

"Later generations have tried (and conspicuously failed) to replicate these wondrous objects with crude acid bathing and paint in an attempt to equal the work of time. We are not taken in"

The Tang Dynasty 618-906 AD

Before we turn to this period, it is worth reflecting that in the 1668 years that spanned the end of the Shang to the emergence of the Tang, including the rise of Imperial China in 221 BC there were no less than nineteen separate entities – tribes you might often call them – comprising the Zhou, Qin, Han, Six Dynasties, Northern Dynasties and the Sui. These rose and fell throughout many regions of China – seldom peacefully. An example of the war-like nature of some of these rules is well shown by the period of The Warring States (474 – 221 BC) Imagine that if you will. Constant skirmishing and disruption for 254 years of unceasing tumult. That trumps our very own Hundred Years War in Europe by a considerable margin. The Tang was a period of artistic advancement, yet still largely focussed upon the idea of burial – much as you would think of Pharaoic Egypt – and what we have above ground today has been disinterred over the centuries. The signature artefact from this time is the pottery horse. There were also camels and human figures too. Musicians, dancers and other useful objects, many decorated with coloured pigments rubbed into the dry clay, and with increasing sophistication, some coloured glazes, principally chestnut, straw, green and occasionally some blue. There were also for the first time sophisticated small bronze articles inlaid with silver, gold and enamel with fantastic symbolic and zoomorphic designs. Everything in fact that the dear departed might need in his or her long voyage into the world beyond this one – as with Egypt also before the Christian era.

Tang Horse. Image © Sotheby's

From the Tang to the Song dynasty, 906 – 1280

906 AD marks the end of the Tang, but before the next major advance and stability of the Song, there followed a further short period of The Five Dynasties (907-960). Running in tandem with that and into the rule of the Song, there emerged both the Liao (907-1125) and the Jin (1115 – 1279).

The Song Dynasty (960-1279)

This rather longer period of 319 years, split into the rule of the Northern Song (960-1126) and the Southern Song (1127-1279) saw a flourishing of experiments with ceramics of all kinds and the improving glazes to go with them. The body of these pieces became increasingly fine, giving rise to the proto-porcelains that emerged at this time, Ding-yao white wares, delicate Qingbai and stockier Jun-yao bowls and the first Longquan celadons amongst them.

Celadon Censer. Image © Sotheby's

The Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368)

Before we take a glimpse at this brief dynasty, it is as well to bear in mind that China - and Japan too – was essentially a closed territory, and the substantial and irreversible involvement of the West with all its implications for Trade, The Arts and Religion, lay largely in the future.

That was however, not the whole story. Not long before the dawn of the Yuan, a child was born, one day to become a global traveller by the name of Marco Polo (1254-1324), the scion of a family of wealthy Venetian merchants. His father’s later exploratory voyage to far-off Cathay (China) was well received in 1269 by the Mongol Court of Kublai Khan (1214-1294), though ultimately the expedition did not bear fruit. They tried again in 1271, this time taking the seventeen year old Marco with them, finally arriving this second time in 1275. The Khan took particular interest in Marco, by now twenty one, and his star rose accordingly. He became Governor of Yangzhou for three years and although the Khan wanted him and his family to remain indefinitely, by 1295 he and they had returned to Venice.

These early cultural exchanges over a period of roughly fifteen to twenty years had sown a seed in the European mind of the prospect of further travel to the east. Ever since the Marco Polo era the imagined scent of spices drifting in from that quarter was palpable. It would only be a matter of time before the flood gates, presided over by the Ming, would open sending Europeans out east in unstoppable waves. A work of art which speaks of this period would have to be one of the first grand blue and white vases or dishes, decorated more palely than in the later Ming and Qing wares. Their natural painting of birds, fishes and flowers within decorative borders was a new departure in the story of Chinese Art.

Yuan Dynasty Fish Dish. Image © Sotheby's

"Ever since the Marco Polo era the imagined scent of spices drifting in from that quarter was palpable. It would only be a matter of time before the flood gates, presided over by the Ming, would open sending Europeans out east in unstoppable waves"

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

Change was afoot and this long period of Chinese history coincided with the European Gothic, the Renaissance and only came to an end a few decades short of the 18th century Enlightenment and later the Industrialisation of the whole world at the beginning of the 19th century. By now, European navigators had begun to explore every corner of the known and increasingly the unknown world, the best known being Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), Ferdinand Magellan (circa 1480-1521) and Vasco da Gama (circa 1469-1525) While these three contemporaries went about their business, China could not help but be influenced by such a growing world force.

Throughout the period of the Ming increasingly subtle workmanship and the pursuit of quality manifested itself through a wide variety of artefacts, including, (but not limited to) bronzes, ivories, jades, cloisonné enamels, scroll paintings, cinnabar and coromandel lacquer work, silver and fine Huanghuali religious and domestic furniture. Added to this exalted list there was also a burgeoning of the art of new brighter porcelains emanating from the kilns and decorators’ workshops of Jingdezhen. None more sublime than those pieces decorated in underglaze blue and white.

Cinnabar Stem Cups, Image © Bonham's

Pair of Chairs, Image © Sotheby's

Blue and White Bowl. Image © Sotheby's

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

The later part of the 17th century and the whole of the 18th century saw what is arguably the absolute summit of finesse in the creation of the decorative arts of China. This was driven by two disparate but equally powerful factors. First there was the striving for perfection in supplying the Imperial Court with exquisite objects, and also to those hierarchical layers of the Mandarin classes which supported the empire. Second was the enormous upsurge of commerce and trade with Great Britain, Europe and the West. Having discovered true porcelain many years before anyone else, an insatiable demand arose in the West for all things Chinese and vast trading empires sprang up, shipping back ceramics on an industrial scale. Chief amongst these from the 17th into the 18th century and beyond, two great mercantile entities came into being. In England, “The East India Company”, (1600-1874), and concurrent with it, the “Dutch East India Company, Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie” (VOC 1602-1799).

Of course the Export trade was also fuelled by the many other goods which China produced, such as tea, silks and spices. The vast loads of porcelain though, Blue and White, Famille Verte, Famille Rose, Famille Jaune and rarest of all Famille Noire all came westwards, and by and large, allowing for losses, are still with us today. This exported porcelain was stowed in the lowest parts of the ships – as ballast almost – whilst the lighter goods occupied the decks above, to trim the vessels for the long leg home.

Pair of Jars with Covers with Famille Verte Decoration. Image © Sotheby's

All that material was intended to leave China immediately, but the strictly Buddhist inspired ceramics and other ‘Chinese Taste’ works of all kinds produced for the Chinese themselves were not part of this Export endeavour. These things, including fine jades, cloisonné enamels, Buddhist bronzes and other works of art only came in part to us by virtue of the highly educated western collectors, operating mainly after 1850.

The reigns of the three consecutive emperors marking the high point in both cases were:

The Kangxi Emperor (1662-1722)

The Yongzheng Emperor (1723-1735)

The Qianlong Emperor (1736-1795).

Jade Vase with Cover. Image © Sotheby's

A Pair of Fang Gu Beaker Vases. Image © Sotheby's

The 19th century initially continued much as had the preceding ones, though gradually, as middle class Europeans came to outnumber and then replace the earlier aristocrats, the quality of those items for export – aimed at greatly larger numbers (though perhaps less discerning) fell away so that by 1900 much of what was being produced was, in comparison to the creations of those glorious past years, mere bric-a-brac. Simultaneously it gradually became clearer that the rampant commercialisation and politics of the early 20th century finally did for the tottering ecifice that had once been the all-powerful Empire of China, and in 1911 it all came to a shuddering halt with the dismissal of the Last Emperor, Puyi (1906-1967).

The Republic of China 1912 - 1949 and The People’s Republic 1949 – the present

The following year, 1912, saw the creation of the Chinese Republic, which ultimately led in 1949 to ‘The Long March’ on Beijing of Mao Zedong (1893-1976) and the seizure of power by the Communists.

As a footnote, the last twenty years has seen determined efforts on the part of modern day China to repatriate as much of its lost tangible history by combing the West to retrieve as many pieces of its artistic culture as possible. These objects had been ‘acquired’ by Europeans from the middle of the 19th century into modern times.

Though as I look around me, there appear to be a few they have missed.

The author of this article is our senior Chinese Art Expert. Our expert specialises in Oriental art, including Chinese, Japanese and Korean. He worked for Spink and Son Ltd, founded in 1666 an auction company for antiques and collectibles, where he was director of the Oriental Department until 1995. He then left to set up his own business, offering select high quality items for direct purchase, and advising clients on the formation and disposal of specific collections.