Vintage Bird and Flower Prints

written by Jasper Jennings

Once a scientifically valuable visual representation of flora and fauna, today vintage bird and flower prints are finally praised for their artistic value and are becoming one of the favourite genre for prints collectors. Read about the history of natural history prints and tips on how to get them!

Banana tree flower (Musa paradisiaca) with io moth (Automeris liberia), Maria Sybilla Meriaen, "Over de voortteeling en wonderbaerlyke veranderingen der Surinaemsche insecten", Merian, Maria Sibylla, 1647-1717, Sluyter, Peter, 1645-1722, Transfer engraving, hand-colored, 1719, From Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (Insects of Suriname), Dutch edition. Photo by: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Beginnings

Ever since the Renaissance, when truth to nature in art and empirical observation in science were paramount, birds and flowers have been given special attention. Western Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw the birth of the professional illustrator, as book trade networks expanded. Nature inspired some of the most lavish publications from the early printing presses.

Fulfilling a similar function to today’s documentaries by naturalists such as Sir David Attenborough, herbals and illustrated works of botany and ornithology raised awareness of our planet’s biodiversity among a literate public. The mediator was not the camera lens or digital technologies, but the etcher’s needle and the engraver’s burin.

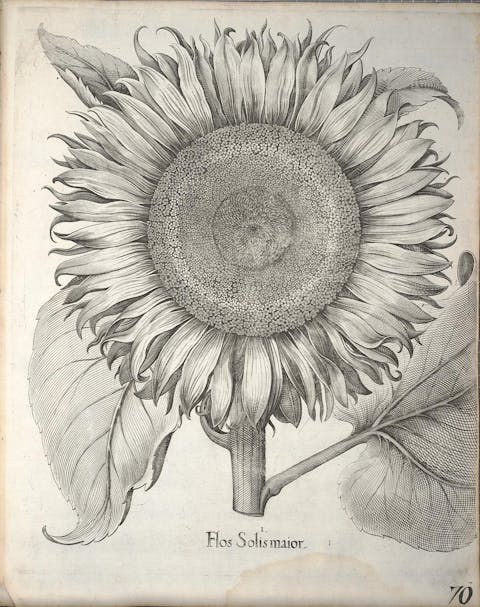

Basilius Besler (1561-1629), a Nuremberg apothecary and botanist, published the first great ‘florilegium’, documenting the greatest garden of his day, belonging to the Prince Bishop of Eichstatt. The plates are both aesthetically pleasing and, for the first time, fit for scientific identification purposes.

From Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis completed 1613. Good impressions from the uncoloured editions (printed into the early 18th c.) can be had from a few hundred dollars/pounds. Image: Flickr /License: Public Domain

The Hortus Eystettensis depicts over 1,000 flowers, representing 667 species, many of them for the first time. Some were newly imported into Europe from America and the Ottoman Empire. The garden itself has been reconstructed and was opened to the public in 1998.

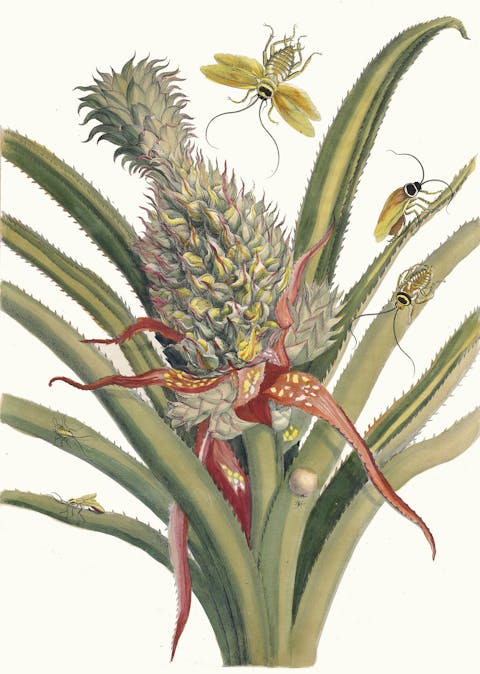

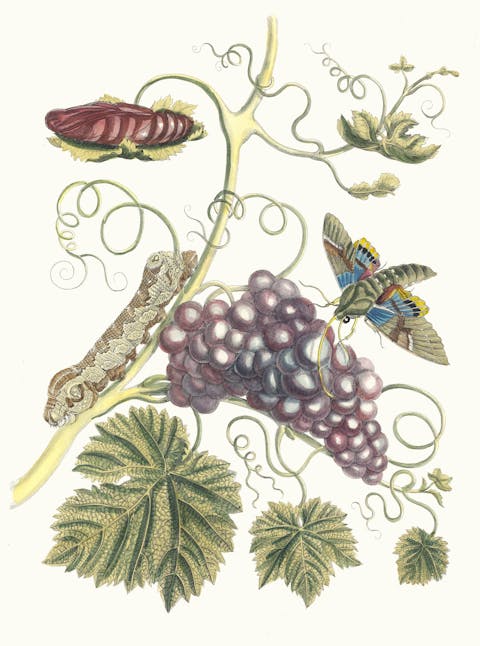

Ecology

We are all aware in our age of the interdependence of the different species that make up ecosystems and of threats posed by human activity. Pioneers like Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) and Mark Catesby (1683 – 1749) recognised this and depicted animals and plants in realistic interactions within their habitats, to which they travelled. Of course, attitudes towards conservation have evolved. But Merian and Catesby’s drawings and journals emphasized humankind’s unique position within the natural order and thus responsibility towards it.

"Fulfilling a similar function to today’s documentaries by naturalists such as Sir David Attenborough, herbals and illustrated works of botany and ornithology raised awareness of our planet’s biodiversity among a literate public. The mediator was not the camera lens or digital technologies, but the etcher’s needle and the engraver’s burin."

Ananas. From the Book Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, 1705. Private Collection. Artist Merian, Maria Sibylla (1647-1717). Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Vigne d'Amerique. From the Book Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, 1705. Private Collection. Artist Merian, Maria Sibylla (1647-1717). Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Merian categorically demonstrated that the caterpillar, pupa and butterfly states were phases in the lifecycle of the same insect - the scientific consensus was that one insect gave birth to another then died.

Mark Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, 1754. The first colour plate book describing North American birds. Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

Their work demonstrates that the most striking imagery has always been the result first-hand observation in the field.

Related: Collecting Vintage Posters

Enlightenment

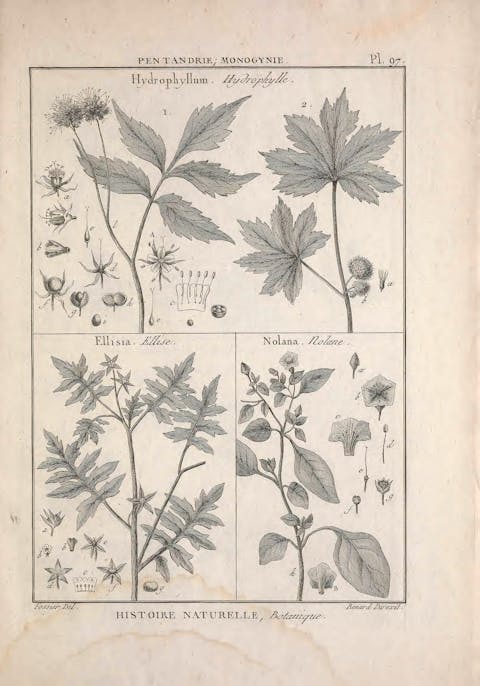

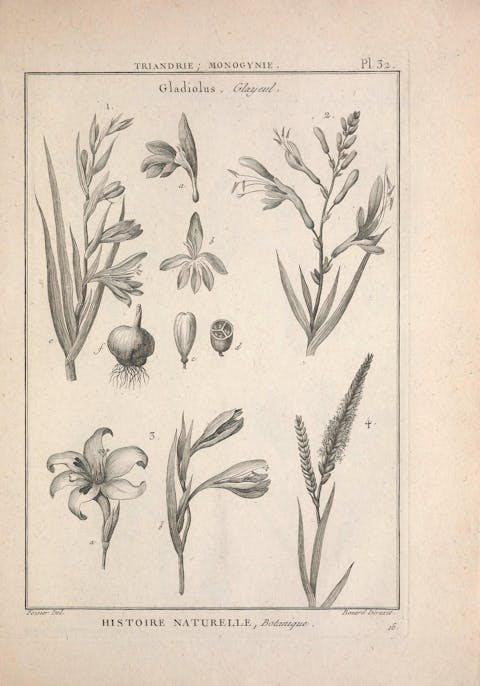

Inspired by Carl Linnaeus’ revolutionary classification and binomial naming systems, the eighteenth century was the age of the great encyclopaedias. Loose plates from Diderot et d’Alembert’s monumental Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1751-65), and the comte de Buffon’s Histoire naturelle, generale et particuliere…(1749-88), are readily encountered on the market.

The typical format shows static specimens arranged on the page in a manner reminiscent of contemporary collectors’ display cabinets. The clean incised lines, lack of background and minimal tonality, produce a graphic simplicity that works well in modern interiors. They can look very effective uncoloured.

Encyclopédique et Méthodique des Trois Règnes de la Nature, Panckoucke, Paris 1791-1823. Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

Encyclopédique et Méthodique des Trois Règnes de la Nature, Panckoucke, Paris 1791-1823. Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

Encyclopaedia plates can be purchased inexpensively. I myself recently bought four sheets from the Tableau Encyclopédique et Méthodique des Trois Règnes de la Nature, published in Paris by Panckoucke 1791-1823 (see images above). They cost a few pounds each. They are framed uniformly in dark wood to complement my bedroom furniture. The modern water colouring on my prints picks up elements of my paint scheme and the whole brings a refreshing touch of the great outdoors, indoors.

Printing colour

As the nineteenth century approached, new technologies, in particular colour printing and the emergence of lithography, heralded publishing projects that were great artistic achievements in their own right. At the same time, voyages of exploration, conquest and commerce introduced plant species from all over the world. The masterwork of Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759-1840), court and flower painter to the French Empress Josephine, was Les Roses (1817 - 24). He depicted the many varieties, including exotics, growing at her estate at Malmaison.

Pierre-Joseph Redouté. Early impressions can sell for thousands of dollars each. His work continues to be popular and is widely reproduced. Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

Redoute’s delicate studies, in watercolour on vellum, became 170 stipples in colour, finished by hand. Vellum lends itself to painstaking detail, the sheen of its surface helping to capture the translucent quality of a flower petal. Special copies of the folio edition of Les Roses were printed on ‘papier velin’ - grainless, silky and smooth paper; they effectively replicate the effect. Les Liliacees (1802 - 15), 503 plates of lilies, is Redoute’s other great book.

Robert Thornton, Tulips plate, from the "New illustration of the sexual system of Carolus von Linnaeus :and the temple of Flora, or garden of nature", 1799-1807, Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

The mezzotint plates in Robert Thornton’s Temple of Flora, or Garden of Nature (1799-1807) – see his Tulips above - are partly printed in colour and finished by hand. Prints from the small folio edition of 1812 are more affordable.

Illustrated periodicals were issued by the various botanical and garden societies that proliferated in the Victorian period, in Britain and the US in particular. Chromolithographs from these can be found inexpensively and make for homely decoration.

Check the latest bird and flower vintage prints auctions on Barnebys here!

Vintage Bird Prints

John Gould (1804-1881), ornithologist and publisher, superintended over 3,000 lithographic plates across 41 volumes, over six decades. He utilised the talents of artists such as Elizabeth Gould, his underappreciated wife, Joseph Wolf, Henry Richter, Joseph Hart, and Edward Lear. The more desirable books revealed the bird life of Australia, New Guinea, the Himalayas and Asia to an eager public; his hummingbirds and birds of paradise are perennial favourites.

John Gould, A Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Humming birds. A complete set of the nine folio bird books formed by Gould's close acquaintance, George Savile Foljambe, made USD 2,458,658 at Christie’s in 2008. Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

Parrots are some of the most threatened avifauna, sensitive as they are to habitat loss. Edward Lear published his own delightful folio on these endearing and characterful birds in 1832, transferring his sketches made at the London Zoological Gardens on to the lithographic limestone himself.

Edward Lear, Illustrations of the family of Psittacidœ, or parrots. One of 42 coloured lithographs. Mid thousands USD per plate. Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

Francois Levaillant (1753-1824) authored five important illustrated books on exotic birds, including one on parrots.

From Levaillant’s Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de paradis et des rolliers (Paris: 1806), drawn by Jacques Barraband. A few hundred dollars each. Image: Flickr / License: Public Domain

Look out for plates from George Edwards’ A Natural History of Uncommon Birds (London, 1748-64) and Eleazar Albin’s A Natural History of Birds (London, 1731-38). Early impressions retail around the low hundreds USD.

John James Audubon’s Birds of America

Published between 1827 and 1838, the 435 hand-coloured aquatint prints transformed bird illustration through life-sized proportions, animated poses and topographical backgrounds. Over 1,000 birds and supposedly 489 species are depicted on the ‘double-elephant folio’ sheets of the single greatest feat in natural history publishing.

It is thought that 119 sets survive today unbroken, only a handful in private hands. The Birds of America project cost Audubon around £100,000 in total - £1.5 million today. In terms of absolute sum realised it is the third most expensive book ever sold at auction: the copy once belonging to the Duke of Portland achieved USD 9,650,000 at Christie’s in 2018. (Top two: The Bay Psalm Book printed in Massachusetts in 1640 at USD 14,165,000 and a 1623 ‘First Folio’ Shakespeare, at USD 9,978,000).

Audubon’s iconic American Flamingo must be the most reproduced bird image of all time. It very rarely comes onto the market singly. Arader Galleries of New York have auctioned individual plates over recent years. A sample of prices realised:

2014: USD 134,200 for American Flamingo

2014: USD 164,700 for Male Turkey (Plate 1)

2014: USD 164,700 for Fish Hawk or Osprey

2017: USD 170,800 for Carolina Parrot (the Carolina Parakeet was declared extinct in the wild in the 1930s due to deforestation, hunting and disease)

2016: USD 176,900 for Roseate Spoonbill (see below):

2019: USD 237,500 for Snowy Owl

2018: USD 266,500 for Hooping Crane

Audubon exemplifies the contradiction of the hunter-naturalist. He himself shot many of the birds he studied, manipulating the taxidermy specimens. Yet his journals express his concern about the impact of hunting and habitat destruction.

The rule of all bird series applies to the greatest: the more colourful and rarely encountered species command the highest prices. The birders’ LBJs (“Little Brown Jobs”) can be yours for a few hundred dollars – the wrens sparrows, thrushes, warblers, buntings, and flycatchers.

The badge of authenticity for seekers of first edition plates is the ‘J. Whatman Turkey Mill’ watermark in the wove paper.

Related: Wildlife Meets Watercolor: Inside Audubon's Birds of America

Robert Havell, Jr.( 1793 - 1878), Roseate Spoonbill from John James Audubon's "The Birds of America", Plate CCCXXI1836, Image: Gift of Mrs. Walter B. James for National Gallery of Art / License: Public Domain

The collector

Old book illustrations of plants and animals can be had for a few dollars per sheet, or even per bundle. Secondhand bookshops will often have a stand or box of loose prints; regular flea markets like Portobello in London, antiques and decorator fairs, book fairs, antique centres, even thrift stores and charity shops, all can yield discoveries.

For the serious collector with deeper pockets there are specialist dealers like Donald A. Heald Rare Books or Arader Galleries in New York City, and Bernard Shapiro or Henry Sotheran in London. Of course, several auction houses have books and works on paper departments.

Strong affinities with the great works of travel and exploration have been noted. Some bibliophiles set out to form whole libraries of natural history. They are often enthusiastic naturalists and travellers. Often, they share a deep appreciation of the art of illustration.

Book collectors instinctively disapprove of book breaking, the shady practice (I think largely ended), of buying a bound, complete volume then selling off its plates piecemeal. There is a renewed emphasis on the integrity of the book as object, and provenance is increasingly important.

Some collect a particular genus or species as represented through time, for example hummingbirds, or toucans. Others collect the work of individual artists/printmakers, who in their eyes capture the essence of their subject. Others are drawn towards the flora or fauna endemic to a particular geographical location.

The buyer fresh to this field is attracted iconographically, and more likely to collect across categories and in different media – sculpture, furnishing fabrics, paintings, taxidermy etc. Are we returning full circle to the eclectic ‘cabinet of curiosities’ model?

"Book collectors instinctively disapprove of book breaking, the shady practice (I think largely ended), of buying a bound, complete volume then selling off its plates piecemeal. There is a renewed emphasis on the integrity of the book as object, and provenance is increasingly important."

Caveat Emptor

Many sellers use ‘vintage’ as vague stylistic term to include very recent reproductions. Sometimes it is employed in ignorance, sometimes as an attempt to suggest artwork is older than it is. The reputable reseller will use ‘antique’ to describe only those impressions contemporaneous with their publication date, or at least only prints of genuine age (earlier than circa 1900).

Look for sellers affiliated to trade organisations like the ABA, ABAA (and auction equivalents), from whom the buyer has recourse if goods are not as described.

Start you vintage bird and plant print appraisal here!

Jasper Jennings joined ValueMyStuff as the antique print expert in 2014. He has spent over 20 years as a consultant and dealer. With his natural flair for entertaining, working knowledge and robust scholarship, Jasper lectures to diverse audiences on print culture and art. He joined a shop selling rare prints and books in Covent Garden straight out of university. After a brief spell in a New York gallery, he started trading himself, exhibiting at international fairs as a member of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association. He has written on all aspects of the market for titles such as Historic Houses and the Antiques Trade Gazette.